RAF 86 HARRIS IN HIS OWN WORDS ~ Part I 1947

HARRIS ~ IN HIS OWN WORDS

A POST WAR VIEW 1947

Strategic Air Offensive

15 July 2025

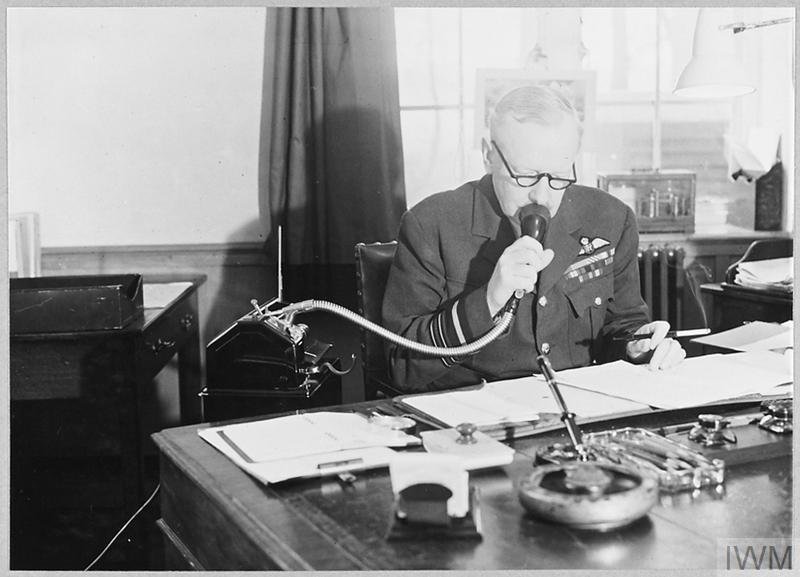

RAF 86 Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Travers Harris

Part I

There are no words with which I can do justice to the aircrews who fought under my Command. There is no parallel in warfare to such courage and determination in the face of danger over so prolonged period, of danger which at times was so great that scarcely one man in three could expect to survive his tour of 30 operations; this is what a casualty rate of five per cent on each of these thirty operations would have meant, and during the whole of 1942 the casualty rate was 4.1%.

Of those who survived the first tour of operations, between six and seven thousand undertook a second, and many a third, tour. It was, moreover, a clear and highly conscious courage, by which the risk was taken with calm forethought, for their aircrews were all highly skilled men, much above the average in education, who had to understand every aspect and detail of their task.

It was, furthermore, the courage of the small hours, of men virtually alone, for at his battle station the airman is virtually alone. It was the courage of men with long-drawn apprehensions of “going over the top.” They were without exception volunteers, for no man was trained for air crew with the Royal Air Force (RAF) who did not volunteer for this.

Such devotion must never be forgotten. It is unforgettable by anyone whose contacts gave them knowledge and understanding of what these young men experienced and faced.

No award could be commensurate with the achievements of the men who flew our aircraft, but I did ask, at the close of the war, that everyone in Bomber Command, both those who flew and those who worked on the ground, should be granted a Bomber Command campaign medal just as the Eighth Army were awarded a special distinction; as it was, the only decoration that most of our ground crews could wear was the "defence" medal.

The British Public’s Sudden Post-War Volte-Face

Few people realise that whereas some 50,000[1] aircrew[2], before and during the period of my Command, were killed in action against the enemy, some 8,000 men and women were killed at home in training, in handling vast quantities of bombs under the most dangerous conditions, in driving and dispatch riding in the black-out on urgent duty and by deaths from what we called natural causes.

These deaths from natural causes included the death of many fit young people who to all intents and purposes died from the effects of extraordinary exposure, since many contracted illnesses by working all hours of the day and night in a state of exhaustion in the bitter wet, cold, and miseries of six winters.

It may be imagined what it is like to work in the open, rain, blow, or snow, in daylight and throughout darkness, hour after hour, twenty feet up in the air on the aircraft engines and air frames, at all the intricate and multifarious tasks which have to be undertaken to keep a bomber serviceable.

And this was on wartime aerodromes, with such accommodation as could be provided offered every kind of discomfort and where, at any rate during the first years of the war, it was often impossible even to get dry clothes to change into between shifts. We never had more than 250,000 men and women at one time in Bomber Command so that the total of 60,000 casualties among our crew and ground staff should give some idea of what the Command had to face in maintaining an offensive for which the great majority that victory might have been more cheaply gained by some other means were awarded the “Defence" medal.

I know that among the people concerned the award was, and is, the subject of much bitter comment, with which I was and am in an entire agreement. Every clerk, butcher or baker in the rear of the army overseas had a “campaign" medal.

subtitle

Every Commander must be prepared to ask himself, after every campaign, whether the results were worth the casualties. The only answer that can usually be given as two points to the contribution which that campaign made to final victory, and it is often impossible to argue, as with most battles of the war of 1914-1919, that victory might have been more cheaply gained by some other means.

But without exception our bomber operations were designed to reduce the casualties of all the services or of the civilian population (as in attacks on the V-weapon industries and sites) and in almost every instance our operations demonstrably had that effect. Without the intervention of Bomber Command, the invasion of Europe would certainly have gone down as the bloodiest campaign in history unless, indeed, it had failed outright - as it would undoubtedly have done.

Without the preliminary bombing, the assault on the German prepared positions at Caen would have cost the army as many lives as an offensive in the 19 14–1918 war, and the capture of the Channel ports, the landing at Walcheren, and the crossing of the Rhine were all operations that could only have been undertaken at a vast sacrifice if it had not been for the intervention of power; as it was, these enormously strong positions were taken with astonishing ease, and at Le Havre for example, which was captured after a week’s bombing, 11,000 prisoners were taken for a loss of 50 allied soldiers.

Sea battles between modern battleships, which are not to sink until after they have become red hot furnaces, are often indescribably horrible; a few bombs on the German Navy in its bases largely put an end to such warfare.

As to our main offensive, the extent to which it saved the lives of the armed forces on every front by depriving the enemy of weapons is less easily calculable. But no one can doubt that it was enormous; the incidental effect that the German Air Force was kept out of the battlefields as well as prevented from bombing England in the latest stages of the war, must by it itself have saved innumerable lives. It cannot therefore be doubted that every one of the 60,000 of Bomber Command who died saved many of his fellows by his death; over and above this is to be added the contribution of all our multifarious operations to the final victory of the allies.

End of Part I

Strategic Air Offensive

By

Sir Arthur Travers Harris 1st Baronet, GCB, OBE, AFC

Note

This is Extract One written by Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Arthur Travers Harris in his published work strategic offensive in 1947. He is direct and to the point.

It's possible that the remarkable eighty-year peace dividend experienced since World War II has lulled younger, post-war historians into a false sense of security. This unique historical context might be leading them to unfairly scrutinize the actions of crucial and highly capable commanders from that era.

By contrast, all the men and women who served within his Command held him in the highest respect, and I have had this testified to me many times both in my own RAF VR post war service and when meeting clients as they approached the end of their lives and I was drafting their wills or helping them to construct their will trusts for their descendants. I didn’t know it then, but I do now ~ I had a ringside seat of so many departures of the Greatest Generation.

It is, though, sensible to express varying views. We are a vibrant democracy and we are therefore able to express our views leaving the populations of less tolerant regimes slightly mystified.

Consider this short extract by Flight Sergeant Harry Lomas in his memoir One Wing High published in 1995 by Airlife Publishing Ltd. It relates to the subject of Tours ~ the number of operations or trips that any crew must complete consecutively before being given a lengthy stand-down period prior to commencement of the next operational tour. It is a very sensible observation that by no means expressed rebellion.

One Wing High

by

Harry Lomas DFM

Extract from page 139

The other item concerned us all, since it involved a new system of scoring a tour of ops. Originally, a tour consisted of thirty completed ops, followed by a rest tour of at least six months, and a second tour of twenty more trips.

Then a refinement had been introduced whereby a Germany trip earned four points, while a target in occupied territory rated only three: a total of 120 points was required. Few argued with the principle involved - that in terms of sweat and stress, a flog to Berlin and back was worth far more than, say, a quickie to a flying-bomb site near the channel coast.

Now the requirement had been upped to 144 points, equivalent to another six German targets. We decided that this was a pretty poor show, especially when one considered the large number of new crews currently being churned out by the training units.

We ourselves were so far removed from the end of our tour that the question was merely of speculative interest; but to a crew sweating it out on their final trips we felt it would prove a very considerable imposition.

We expected better of ‘Butch’ Harris.

End of Lomas DFM Extract

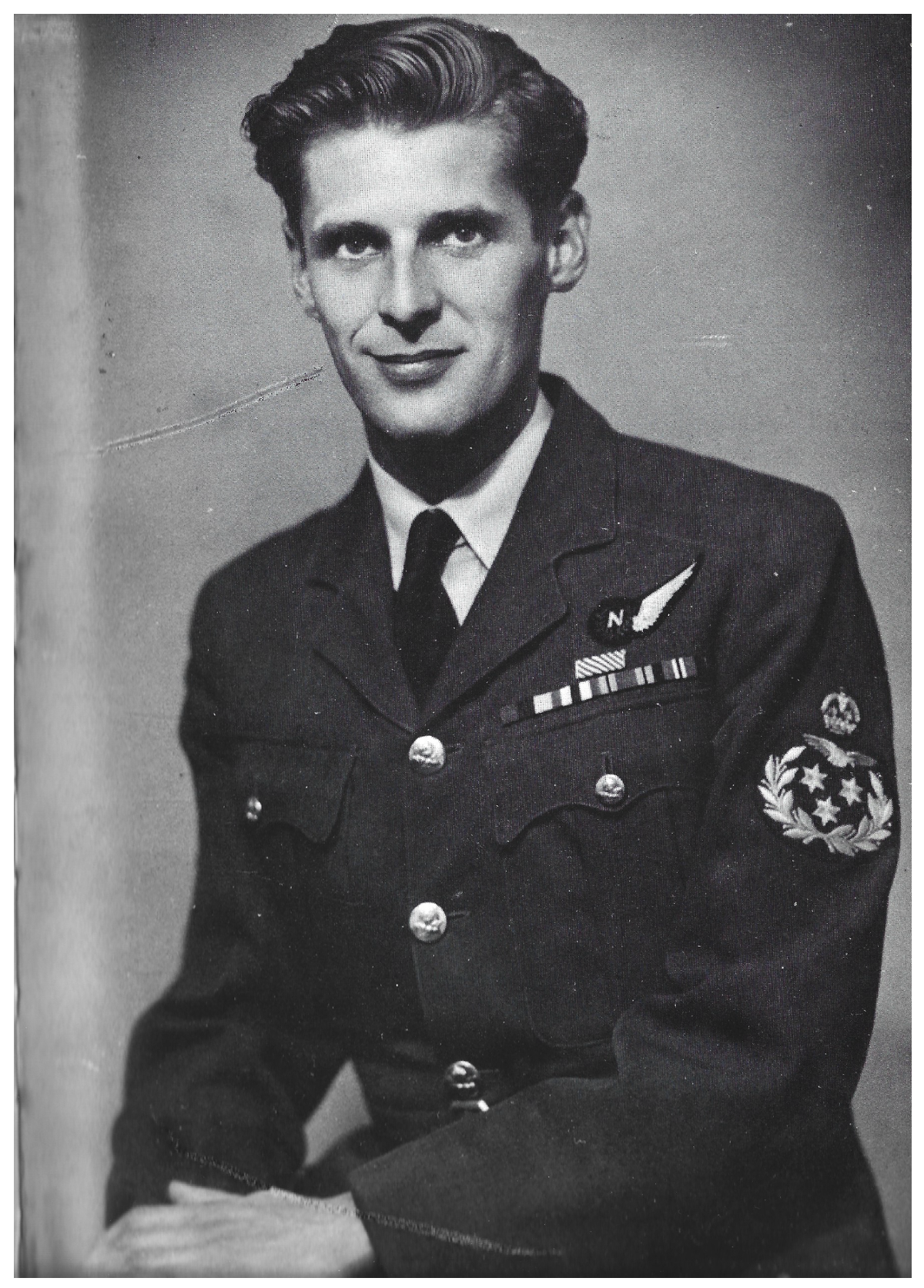

Flight Sergeant Harry Lomas DFM RAF

Handley Page Halifax Navigator on the Anderson Crew

Flight Lieutenant Keith Anderson Captain,

Royal Australian Air Force

15 July 2025

Liverpool and Gloucestershire

© 2025 Kenneth Thomas Webb

Footnotes and Citations

[1] 55,573 is the officially recognised number of deaths on the battlefield. Compare this with the first day of the Battle of the Somme, July 1, 1916, upon which the British Army suffered 57,470 casualties. This included 19,240 fatalities. The total losses of RAF Bomber Command was only 2,147 fatalities short of being three times the number of Somme fatalities. KTW. Using online data from bbc.co.uk/teach articles.

[2] My father (Desmond Webb) often talked of his elder brother’s comment whilst on home leave in early 1943 “that the average life expectancy was four ops”. Dad would have been 16 and at that time in a wartime reserve occupation. I suspect, though, that he overheard the conversation between his two brothers Ken and Arthur. Arthur was 13 years older than Des, but only 5 years older than Ken. Arthur was also married and likewise in essential wartime industrial production. I can, though, picture Dad quite easily taking things in like a sponge. Dad was very sensitive, my sisters and I loved Dad for this, and I always knew that what he was reporting to me was not circumstantial or hearsay evidence, but direct evidence, that which did indeed lead to the arrival of the dreaded priority telegram. KTW

[3] This Paper’s principal image is by courtesy and special permission of the Curator of the Imperial War Museum of which I am a fully subscribed member. The Image is IWM CH 005494 (KTW)

Commenced 4 June 2025